By the winter of 1916/1917, the Russian army, economy, and country was in a shambles. Over 2 million soldiers had been killed in the fighting, millions more wounded. The tsar’s policies had resulted in food and fuel shortages and rampant inflation. By early March, the population of the capital of Russia, Petrograd (St. Petersburg), were fed up. On international women’s day in 1917, the workers began to strike and protest, filling the streets with tens of thousands of people. More joined each day including 170,000 nearby garrisoned troops. Workers broke into arsenals and took rifles. The capital was in chaos and the worker councils (called soviets) demanded the abdication of the tsar. This was a true peoples revolution. By the middle of March, Nicholas II abdicated to his brother who abdicated the next day.

All the Soviet leaders we’ve heard so much about from Russian history such as Lenin, Stalin, and Trotsky weren’t involved in any of this. They were still in exile during the March revolution. They rushed and connived ways to get back to Petrograd as soon as they could. Stalin was the first to arrive and immediately resumed his old post as editor of Pravda, the Bolshevik newspaper. In the beginning of April, Lenin made it back to Petrograd and took control of the Bolshevik party. The Bolsheviks were one of many parties and players at the time. They soon became major players. Trotsky arrived in Petrograd in May. All summer and into the early fall, there was a power grab by the various parties including the Bolsheviks. By this time Lenin was in charge and planning for an armed rising within the provisional government. In the end of October, they were successful, but violent encounters between the various players continued.

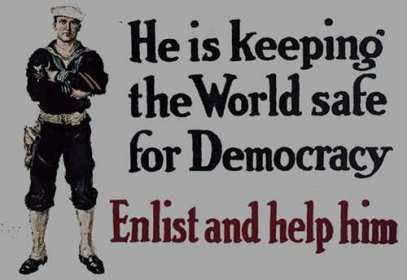

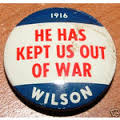

In the middle of November 1917, Germany and Russia began negotiations for an armistice which soon followed. The end of November marked the beginning civil war in Russia that would last for four years with the Bolsheviks (communists) finally victorious. The armistice with Germany in the winter of 1917/18 allowed the Germans to move all their troops from the Eastern Front to the Western Front. The Germans hurried an offensive in France during the spring of 1918 in hopes of complete victory before the Americans could build up their troops in Europe. They weren’t successful, and by the summer of 1918 over 2 million American troops were in France.

History does not speak kindly of Nicholas II, the last tsar of the Russian Empire. He did not heed the warnings of Revolution from earlier protests and never instituted substantive changes in the government or the civil side of society. He blundered into the war, like so many of the other leaders at the time, refusing to see the reality of his own military might and those of the enemy. He and his family were put under house arrest in the spring of 1917 and executed by the Bolsheviks in 1918.